What follows are the first two parts of a four-part essay I published back in 2021 in Genuine Gold, a literary magazine. As we are heading into college graduation season, and as higher education finds itself the target of the Trump administration and conservative politicians nationwide, I offer this essay on the history of college in films, television, and popular culture. We all know what college is for, right? But what about the college film? What psychic or cultural work do these media objects perform? What impact have they had historically? I hope you enjoy! Thanks for reading.

Most people know nothing about higher education. And this is doubly true for college grads.

It’s totally understandable. Even in its most essential functions, academia seems a world removed from the realities of most working Americans. In a hyper-capitalist society like ours where people can be fired for just about anything, it takes a considerable amount of intellectual (and intestinal) fortitude to take the time to learn about, say, the intricacies of assessment or how tenure works. (It is far easier and much more satisfying to simply call for tenure’s abolishment.) The average worker has gained a smidge more bargaining power here lately, thanks to a nationwide labor shortage and the so-called “Great Resignation.” But in an economic sector still obsessed with metrics and the bottom line, meetings-that-could-be-emails, and the ritual performances of busywork, the college professor’s supposed devotion to “the life of the mind”[1] can seem positively quaint by comparison, like barn raisings and leaving pies on an open windowsill to cool. (Never mind that such an existence is exceedingly rare even for most faculty.) Higher education, from the funky medieval robes to the unfamiliar patois of credit hours and transfer courses to the mythology of “summers off,”[2] remains a mystery wrapped in an enigma ensconced in an abundance of tweed.

(Just kidding. Nobody wears tweed anymore.)

And so, as with so many other things, we turn to film and television to get our fix on reality and, at the same time, to escape it. After all, movies and TV have long been the cultural touchstones that can reach across the aisle and across generations. They teach us about ourselves, our values, our fears and anxieties, and our tolerance for difference (or lack thereof). In the case of higher education, films and television offer a window through which one can glimpse a stylized, fictional version of university life. But don’t think for a second that these fictionalized depictions are accurate portrayals of the ivory tower—far from it. In fact, most films and television shows get so much wrong about college life that it’s useful to tease out from their missteps and fabrications just what the reality is. Now that Netflix’s The Chair is re-opening conversations about college life and our First Lady is heading off to the community college classroom every day—heck, even the plot of Spider-Man: No Way Home employs a lengthy set-up involving the college application process—the time seems right to revisit how the hallowed groves of academia have been portrayed in movies and TV.

2.

Recently, during a long-overdue chinwag[3] with a friend from Cornwall, I was reminded of a simple fact about our friends across the pond that is often overlooked. When Brits, Canadians, and the more “European-minded” among us talk about higher education, they talk about “university,” as in “She’s going to university at King’s College London on a Perseverance Trust Scholarship.” The phrase itself practically drips with British-ness, at least to the American ear, like serving hot scones with glowing dollops of orange marmalade or spelling “color” with a “u.”

“Going to university” sounds more like a plan, a legitimate course of study complete with academic aspirations and impressive masonry work.

“In the fall I plan to go to university unless father sends for me; in which case I will work as a foreman in his munitions factory.”

Pass the mortarboard...and grab me a scone.

Americans, on the other hand, preternaturally suspicious of anything that smacks of raised pinkies, tend to stick with the more pedestrian and distinctly Yank-ified phrase “going to college.”

“Where ya going to college?”

“I’m at State.”

Conversation over, next topic.

The American phrase conjures images of that magical four- to nine-year period in a young person’s life when they finally escape the hyper-surveillance of the typical American prison system high school, cast aside the shackles of suburban middle-class domesticity, and embark on an extended period of fun, frivolity, football, and casual sex. At least, such is the vision of college life that emerges from the very long list of more than 200 films and television series that purport to depict the American collegiate experience in all its hallowed glory.[4]

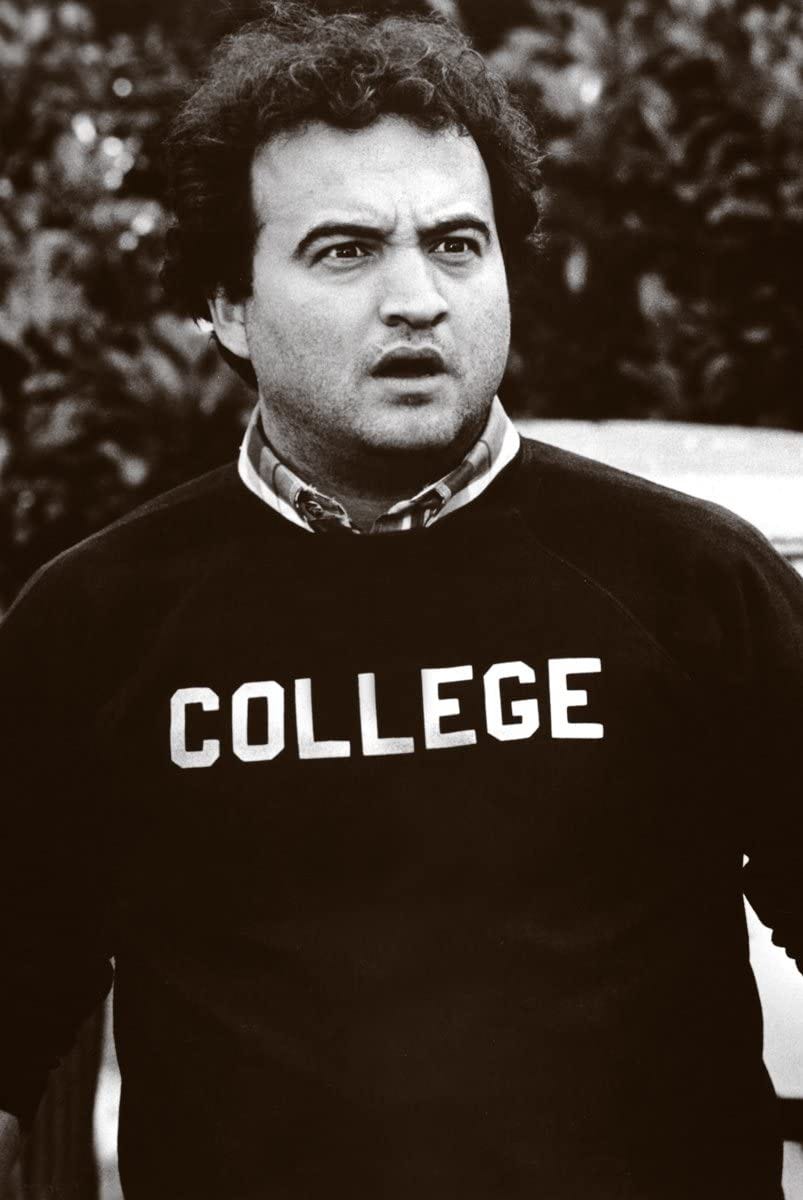

The word “college”—though decidedly more pedestrian—is nevertheless capacious in its scope. It can refer at once to the hallowed halls of our finest Ivy League institutions, as portrayed in films like Good Will Hunting (1997, Dir. Gus Van Sant) and Legally Blonde (2001, Dir. Robert Luketic)—both set at Harvard (pronounced Hah-vurd)—just as it can refer to raucous binge-drinking sessions with a guy named Bluto, as portrayed by the immortal John Belushi in Animal House (1978, Dir. John Landis)[5], a film that practically wrote the first draft of every single college movie script going back forty years or more.[6]

The college film provides the backdrop for all these fantasies and subconscious misremembrances. In Academic Ableism, Jay Timothy Dolmage acknowledges this connection, writing that college films “show…not really a reflection of what happens at universities, but instead disclose some sense of what our culture thinks colleges or universities should be like—and this in turn does influence or frame expectations of what the experience of college or university will be” (155; emphasis mine).

For nearly 100 years, conventional wisdom held that college movies provide a kind of escapism for the viewer. If you never went to college, then you can partake vicariously in the on-screen exploits: chugging along with Bluto or scheming your way into sexy situations with the gang from American Pie 2 (2001, Dir. James B. Rogers)[7]. If you did go to college, you can indulge in the film as an extension of that cherished time and as a safer, saner way to enjoy the bacchanal long after the final peals of “Pomp and Circumstance” have gone mute. Films and TV shows about college fascinate us precisely because they purport to pull back the curtain—albeit in a fictionalized fashion—on a time in our lives that few of us remember except perhaps through a hoppy, malted barley haze.

We love fictionalized portrayals of college precisely because, the story goes, they allow us to relive these special years, and they represent the freedom that comes with being, for the first time, truly in loco parentis[8]. In a New York Times interview from 2003, Landis reflected on the runaway cultural success of Animal House and offered a simple theory for the long-lived popularity of movies about college: “Remember, our fathers' generation used to talk about World War II as the best years of their lives. Why do people romanticize the military and romanticize college? You're 18, and you're out of the house” (qtd. in Mitchell).

Another theory for the popularity of college films and TV has to do with youth’s inherent beauty. As Andrew C. Miller writes, “university campuses provide an ideal and idealized location in which to construct romantic narratives of attractive young men and women” (1224). Would Legally Blonde be the same film without a young Reese Witherspoon’s buoyant blonde attractiveness? Doubtful. Would Good Will Hunting have won two Academy Awards and ascended to the top of many “Best College Films”-lists without the benefit of Matt Damon’s chiseled biceps moving a mop around a classroom building?[9]

And what of the scenery? College campuses are known for their breathtaking, bucolic nature, their manicured lawns, and wind-swept quads adorned with the golds and reds and yellows of brilliant autumn—to say nothing of the red brick buildings, wrought iron gates, and neo-Gothic monstrosities covered in ivy.

These are all fine theories. But they’re wrong. The real reason for the popularity of college films is even deeper and more psychologically subterranean: college films are like fun house mirrors. They contain the seeds—the essence—of all our guiltiest fantasies, albeit in ways that are slightly bent, exaggerated, and refracted against the cold harshness of reality.

Thanks for reading! I’ll drop the rest of the essay (parts 3 and 4) in a few days.

Notes

[1] Thanks to Joel and Ethan Coen’s brilliant 1991 film Barton Fink, I can never write these words without picturing John Goodman screaming maniacally “I will show you the life of the mind!” Great flick if you haven’t seen it.

[2] To avoid being absolutely gutted by my colleagues in higher education across the US (and the Twittersphere), I must point out that “summers off” (note the quotation marks for extra irony) are themselves a mostly mythical beast. Most academics I know work like dogs in the summer preparing for courses in the fall, finishing up work from the spring, writing books and articles to keep their jobs, feverishly posting cryptic messages to social media about how they should be more productive, and so on. The myth of “summers off” is really just another Republican boogeyman intended to scare small children and the elderly, like Critical Race Theory or Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.

[3] Chinwag: n. and v. slang (a) n. chat, talk; (b) v. slang, to talk, chatter. (From the Oxford English Dictionary.)

[4] Ironically, the way Americans use the word college is more capacious than the British-European-Canadian tendency towards “university,” even though, if we are getting technical about it, a college is either a school within a larger university structure (more on this below) or a stand-alone institution of higher learning that focuses on doing one thing very well, like a liberal arts college, say, or a clown college. (Or a barber college!)

[5] It is really no exaggeration to say that Animal House may be the most recognizable film about college ever made. John Belushi’s iconic party animal Bluto, a character who throughout the film engages in far more chugging than conversation, sports a crew neck sweatshirt that simply—and essentially—reads “College” during a particularly alluring scene in which he chugs an entire bottle of Jack Daniels (widely rumored to be actual whiskey). Today one can purchase a replica of Bluto’s iconic sweatshirt for around $60 online. Ah, late capitalism.

[6] Animal House was not set at Harvard but, memorably, at the fictional “Faber College,” a school that one commentator wrote is “an institution of higher learning apparently named after a pencil” (Mitchell).

[7] You may be asking: “What about the first American Pie film?” Since the OG film was set in high school, it doesn’t count here. The much-anticipated sequel, American Pie 2, is the first film in the series to be set during college—in the summer after the first year of college, to be precise. A magical time in the life of any young reveler.

[8] Another hoity-toity term—this one in Latin—that basically means “no parents, no rules.”

[9] According to a quickie Google search and back-of-the-envelope math, Good Will Hunting appears in the top five of 19 lists of “Best College Films” of all time.