Higher Ed's Obsession of the Decade: Enrollment

For many faculty at public regionals and non-elite SLACs, "enrollment management" has become yet another job in an already overstuffed portfolio.

The Cold has arrived.

Not only has The Cold arrived, it has kicked off its shoes and plopped down in your living room. Right now it’s in the kitchen, rummaging through your fridge for sandwich fixin’s.

Miracle Whip? Eh, I guess that’ll work.

Got anything other than rye bread?

Last Thursday was Groundhog Day. Not to be confused with the purely hilarious 1993 Bill Murray film of the same name, Groundhog Day is quite possibly one of the cruelest hoaxes ever perpetrated on people who live in cold weather climates. (Don’t even get me started on the poor animals themselves who get annually abused by Dickensian men in stovepipe hats—please note that I wrote “annually.”)

Why is it so cruel? Because Groundhog Day is a basically a massive practical joke played on people who live in cold climates like the Midwest. Cold enough for ya? Well, there’s six more weeks of it! Harharharharhar. Better settle in!

Here in Indiana, realistically, we are in for way more than six weeks of winter. It’s not unusual to get significant snowfall in April, and you don’t really get anything approaching warmth and sunshine on a regular basis until mid-May or later. Memorial Day weekend is generally thought of as the “safe zone.” If the Indy 500 has arrived, then you can rest assured that you’re done with snow and subfreezing temperatures. But not until then.

Meanwhile, people in the South have been wearing shorts and flip flops since the end of January.

The Cold invaded a bit early this year. On Christmas Day, we had scary cold temps, like everybody else in the country, and the mercury fell to ten below here in Indianapolis. I had just returned from a trip to Arizona with my brother, and I remember having that familiar thought, one that comes and goes frequently this time of year, pretty much non-stop from Thanksgiving through Memorial Day: Why do people live here?

This is not merely the idle complaining of a Southern-born kid who can’t handle the cold. (Although, yes, it is that, too.)

My complaining about The Cold actually has a constructive purpose, and it has to do with perhaps the greatest existential crisis currently facing public regional universities (like IU Kokomo) and non-elite, flagship institutions (including both public and private universities) in the Midwest and Northeast regions of the US.

To put it bluntly, no one wants to live here anymore. And this simple fact—alongside a significant decline in birth rates in the aftermath of the Great Recession—threatens to be the undoing of a great many colleges and universities in the coming decades, from western Pennsylvania to the Great Plains. It’s simple math. People aren’t moving here; they’re moving away from here. Those who stay are having fewer offspring.

At my own institution, one of those vulnerable public regional universities you read so much about in the higher ed press, everything has been subsumed by the steady drumbeat of enrollment concerns. I mean everything. Sure, we talk about our research and teaching and microcredentials and ChatGPT and intellectual exploration and other things related to the enterprise of higher education, but there’s always an academic middle manager there to bring the conversation back down to brass tacks. Everything comes back to enrollment.

“Butts in seats,” as they say.

To put it bluntly, no one wants to live here anymore. This simple fact threatens to undo a great many colleges and universities in the coming decades, from western Pennsylvania to the Great Plains.

A few years ago I was in a stage production of West Side Story. I played Doc, the older, adult character who acts as a mentor to Tony, the main protagonist of the musical. (Doc was originally played by Ned Glass, one of the great midcentury character actors of American stage and screen.)

If you know the musical, you know that much of it involves two groups of people standing on either side of the stage and sort of chanting at each other while dancing and snapping their fingers. (This description would probably suffice for a great many Broadway musicals, but it definitely captures the essence of West Side Story.)

In my mind, this depicts the dynamic between faculty and administration that has existed at regional universities for a decade or more:

Sharks (Administration): Enrollment!

Jets (Faculty): Research!

Sharks (Administration): Enrollment!

[Finger snaps.]

Jets (Faculty): Intellectual pursuits!

Sharks (Administration): Enrollment!

[Finger snaps.]

Jets (Faculty): The life of the mind!

[More finger snaps.]

Sharks (Administration): Enrollment!

Jets (Faculty): Teaching and learning!

Sharks (Administration): Butts in seats!

It’s not that I’m too thick to understand the essential reality that enrollment is what keeps us employed. I understand why admins, higher education watchers, and others are so concerned about this existential reality.

But the open questions for me are these: (1) to what extent should enrollment be part of a rank and file faculty member’s overall employment portfolio? I wasn’t hired to be an enrollment manager, which is itself a neat little euphemism, as though enrollment was something that needed managing. What it really means is quit standing around and go find us some students!!!

And (2) to what extent should enrollment concerns completely and totally eclipse other essential elements of the public university operation?

And, relatedly, are we shooting ourselves in the foot and missing out on opportunities for institutional advancement and creativity by focusing so myopically on enrollment as the only metric of success that really matters anymore?

These are complicated questions that I hope to address outright in future newsletters. In this post, I want to focus specifically on the changing dynamics of both demographics and funding for higher education that have led to this situation.

Rust Belt Realities

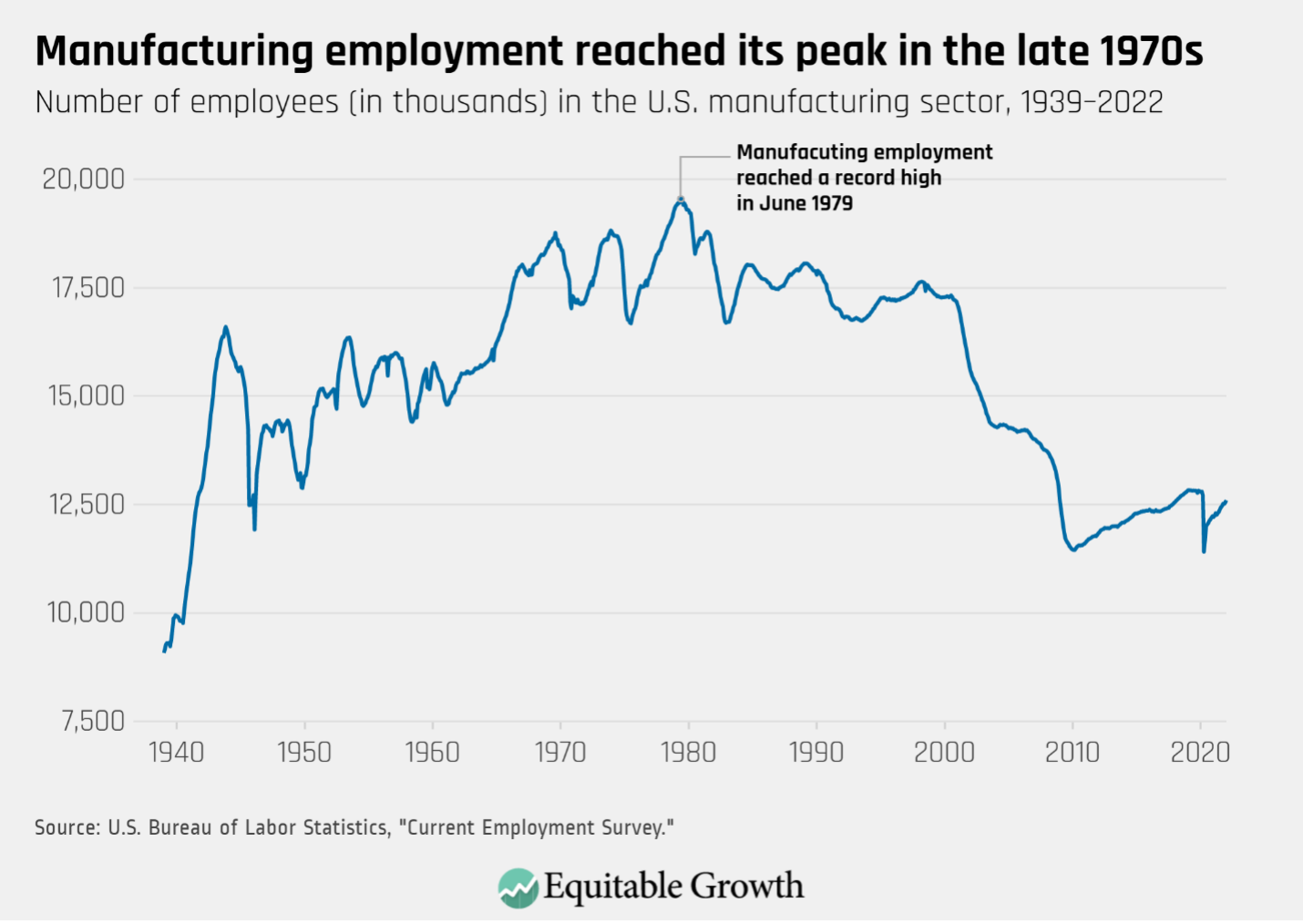

For much of the 20th century, the Midwest was the country’s heavy manufacturing center. Then suddenly, it wasn’t.

Everyone knows about Detroit and its spectacular fall from grace, but what you might not know is that there were at one time hundreds of mini-Detroits dotting the map all over the Midwest, from Youngstown, Ohio (steel production) to Kokomo, Indiana (automotive parts and assembly) and in scores of other small and medium-sized communities, where hard working people made everything from raw materials to finished appliances and automobiles.

A combination of offshoring, a decline in the power of organized labor, and bad (often tragically short-sighted) economic and tax policies at both the state and federal levels led to the demise of what is known as the Rust Belt, an area of heavy manufacturing bordering the Great Lakes region that saw the single largest decline in economic activity of any region in the US between 1950 and 2000.

A major cause of offshoring in manufacturing, which began in earnest in the late 1970s and picked up steam through the 1980s and 90s, was the ideological conviction, articulated by GE’s former chief Jack Welch, that corporations’ first allegiance was to their shareholders, not to their employees or to the communities that supported them. The practical result of this mindset was that if a company’s stock value could be boosted by cutting labor costs and moving its manufacturing operations to Mexico, then the CEO had an ironclad duty to do so. Enriching the shareholders and making a beautiful dollar for the executive class became the sine qua non of American corporations throughout the 1980s and 90s.

Communities and workers be damned.

This dovetailed with the start of Ronald Reagan’s two-term presidency in 1981, and his neoliberal goals of de-regulating the economy and shredding the social safety net.

Both of these ideological convictions—enriching stockholders and de-regulating the economy—were in turn built on a set of economic assumptions that marked a sharp right turn away from the Keynesian policies that had shepherded most of the industrialized world through the tumult and social upheaval of the 20th century. Known as “neoliberalism” (i.e., “neo” as in new and “liberal” as in classical liberalism in laissez-faire economics—not liberal as in left-wing or progressive), this new economic order was built around the GREAT MARKET GOD and the idea that the social contract began and ended with the individual, not with the public. As Margaret Thatcher, the UK’s version of Reagan, famously said in 1987, “There is no such thing [as society], only individual men and women.”

Here’s the full quote with some additional context:

I think we have gone through a period when too many children and people have been given to understand “I have a problem, it is the Government’s job to cope with it!” or “I have a problem, I will go and get a grant to cope with it!” “I am homeless, the Government must house me!” and so they are casting their problems on society and who is society? There is no such thing! There are individual men and women and there are families and no government can do anything except through people and people look to themselves first.

Reagan and Thatcher together were the public political faces of this new market-oriented set of economic policies that took hold in the public’s imagination in the 1970s and 80s and has only intensified in the decades since.

While whole books have been written about the term, and I can only do a very short, very over-simplified version here, the essential concept is this: there is this quasi-magical force called “the market” or the GREAT MARKET GOD that is unquestionably fair and unbiased because it represents the purest form of democracy—people voting with their dollars (and pounds). The market, moreover, because it is so fair, is what dictates the survival of companies and people and communities; if people fail or if a company fails, that’s because the Great Market God ordained that it fail, either because it wasn’t profitable or it wasn’t working hard enough or it just wasn’t meant to be. (The Great Market God works in mysterious ways, after all.)

Enriching stockholders a la Jack Welch’s dictum is good because that’s what the Great Market God wants. Public programs and higher taxes to pay for them are bad because they just get in the way of letting the Great Market God do its thing (which is good) and give lazy people an unfair advantage.

Regulations on corporations and social welfare programs and government assistance are also bad because they offer people and companies a way to “cheat” the market, sort of like getting into heaven on a technicality. Besides, the fewer regulations and social programs we have, the harder people have to work and the purer and more effective their work will be because the Great Market God always rewards us for our hard work. (You can probably see the connections between neoliberal thought and some dominant versions of Protestant Christianity.)

People themselves become markets, under neoliberalism. And any notion of the good of the collective, of the community, withers away. This is one of the primary goals of neoliberalism. And to my mind, it’s also why so many of us are miserable today.

But I will have to save that rabbit trail for a different post.

So now that we have some ideological background on the shift that occurred in US public and economic policy in the 1970s, what about the Midwest and manufacturing?

These manufacturing jobs that disappeared to Mexico and elsewhere, jobs that were unionized, well-remunerated, and secure, were a big factor in what kept people in places like Youngstown and Kokomo and Dayton, Ohio and Allentown, Pennsylvania. Now, for many people, perhaps especially the young people who grow up in these areas, there’s not much of a reason to be here anymore.

As someone who has lived in the heart of the Midwest for the last decade and grew up in a small town in the deep South, I believe I have a unique perspective. Culturally, the Midwest and the South share a lot of similarities—good and bad. The people tend to be clannish, the politics tend to be deeply conservative (especially in terms of social mores, religion, and “values”), and community is everything (where you from? is even more common than what do you do for work?).

But here’s the big difference between the two regions: people actually want to live in the South. No one wants to live in the Midwest anymore, because…why would they?

And this isn’t just me talking. The macro-demographic trends over the last 60+ years bear it out. In their recent book on the future of higher education, The Great Upheaval (Johns Hopkins UP, 2021), Arthur Levine and Scott Van Pelt show how the South and West are experiencing booming rates of domestic migration, while the Midwest and Northeast are shrinking.

They write,

In 1960, a majority of Americans (54%) lived in the Northeast (25%) and Midwest (29%). A minority (46%) resided in the South (30%) and the West (16%) (US Census Bureau, 1961). Today, the balance is reversed. Most Americans (62%) are now residents of the South (38%) and West (24%). And the population in the Northeast (17%) and Midwest (21%) has dropped off precipitously (US Census Bureau, 2019). And the disparity is continuing to grow.

With these stark changes in demography, it’s no wonder that public regionals and non-elite small liberal arts colleges (SLACs) in the Midwest and Northeast are struggling mightily. The pandemic exacerbated what had already been a dire situation.

But there is more to this story that just geography and demography. Like the offshoring that occurred in the final quarter of the 20th century that decimated small towns across the Rust Belt, economic policy and ideological attitudes about the public and the private have played an outsized role as well.

Economic Woes

It’s no secret that state appropriations for public colleges and universities, the institutions that teach three-quarters of all US college students, have been on the decline since even before the Great Recession. Higher education’s funding woes and the crisis in student loan debt they have caused has been perhaps the biggest higher education story of the last quarter century, the focus of mainstream journalism, countless talking heads programs, blogs and podcast episodes, research reports, webinars, and scholarly books.

The question itself has become a kind of meme: Why does college cost so much?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Highlight Zone to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.