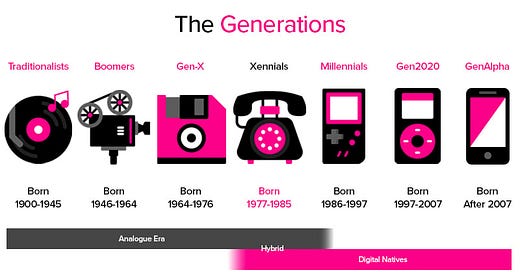

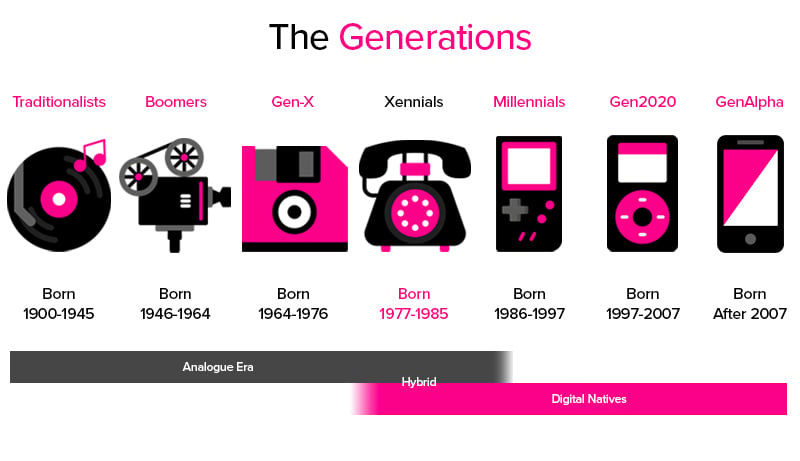

Ever heard of a “Xennial”? Sounds like it might be a secretive race of humanoids living on a far-off planet, perhaps in a knock-off Star Trek-esque universe or something. But Xennial is actually a term for a micro-generation—those born between 1978 and 1982—who were the last to experience a relatively “normal” upbringing in Marshall McLuhan’s Gutenberg Galaxy of print-based media. In other words, we learned to use computers the old-fashioned way: booting from DOS and logging onto AOL—with screeches a-plenty. The Internet was slow, unreliable, and not yet a thriving digital cosmos. Sandwiched between the original Star Wars and its iconic sequel, as Xennial youngsters, we played outside until the streetlights came on, took keyboarding classes in high school, and lived lives not yet entirely governed by the internet and social media.

Did we drink from the hose? Yes, but I don’t remember this being as central to the Xennial experience as social media would have you believe.

As a quintessential Xennial, born in 1980 (on this day!) and right in the thick of it, my academic journey has unfolded in an era marked by profound transition. When I started my PhD program in 2004, the old academic hierarchies were still mostly in place. There were still tenure-track jobs to be had, though far fewer than our GenX older siblings and friends. But the cracks were beginning to show. The internet and social media were opening up new vistas for community, engagement, and networking, just as the academic job market was starting its decline. St. Zuck opened up Facebook for all college students (not just those at the Ivies) in 2004 or 2005. By the time my generation emerged from the academic cocoon, the Great Recession was in full swing, the job market had turned bleak, and we were left to navigate a labyrinthine maze with fewer supports than those who came before us.

Consider the peculiarities of our Xennial upbringing: the majority of us didn't have mobile phones in high school, just pagers. We mastered the art of leaving a callback number on a 3-second recording via 1-800-COLLECT. CDs were king, but they were pricey, so discovering new music often meant burning CDs on a friend's Napster hookup or taping radio songs to play back in our cars. Coding was less about trendiness and more about necessity—something we learned out of survival rather than from a tech bro proclaiming it as the future of work in yet another Medium post.

Given these circumstances, it’s no surprise that Xennials have become adept digital shepherds. As technologist Kyleigh Nevis (2021) puts it, "Xennials are chameleons. They were not raised with advanced technology but rather had to adapt to it. This pseudo-generation can appreciate the rapid emergence of new applications while remaining highly empathetic to those just getting comfortable with the applications they recently learned." This adaptability sits at the sweet spot where education and technology intersect.

However, while our digital fluency and adaptive capabilities are assets, they haven’t necessarily translated into traditional academic rewards. Academia, with its enduring hierarchies and entrenched norms, has often failed to recognize the unique contributions of Xennials. Instead, we find ourselves navigating a world where the old rules still apply, but with new digital and economic pressures.

Millennials in higher ed have, on the other hand, had a somewhat easier time. (Or as easy as anyone has it in a broken system like academia these days.) They came up alongside mainstream social media shaping reality in both work and play. Millennials have their Twitter support groups and armies of followers hanging on their every idle prognostication or bizarre complaint. They have been able to weaponize social media in such a way that has—thankfully—called attention to many of the inequities (especially for women and people of color) that higher education thrived on for so many decades. Xennials had none of that. When graduate students at the University of South Carolina tried to fight for real healthcare in the late aughts, we were told that “grad students who take up causes like that don’t finish their dissertations.” The message was clear: keep your nose down and get the work done. Millennials, god bless ‘em, they don’t listen to authority like we do.

In the old days, senior faculty typically either wrote books or edited journals. This was the prize of reaching apex predator status in a cutthroat and difficult profession. But Xennials don’t do things the traditional way. Case in point: one particularly rare and amusingly paradoxical aspect of this situation is the phenomenon of senior, tenured faculty members these days taking on roles like reviews editor for academic journals. (Full disclosure: I have served as reviews editor for Across the Disciplines since 2018 when I first received tenure.) In a world where the academic hierarchy often prioritizes traditional accolades and prestige, such roles can seem like an unexpected twist. That is, being a reviews editor has traditionally been a role reserved for junior folks, even graduate students in many cases.

For Xennials, who are used to breaking norms and adapting to new realities, these roles might be seen as both a challenge and an opportunity to disrupt the status quo from within. It’s a bit like using a pager to send a tweet—an old tool used in a new way, bridging gaps and forging connections in unexpected manners.

In this context, the work of Mike Palmquist, founder of the WAC Clearinghouse, provides a compelling example of how Xennials are reshaping academia. Though Palmquist is himself a Boomer—a term that has become weaponized against the older generation such that I almost feel dirty writing this about someone I admire—Palmquist’s passion for open-access publishing is more than just a digital-age trend; it represents a significant shift toward more equitable ways of disseminating academic knowledge. The WAC Clearinghouse, which Palmquist established, is dedicated to promoting open-access publishing, making scholarly work freely available to a wider audience. This approach challenges the traditional paywalled models of academic publishing, which often restrict access to those who can afford hefty subscription fees or institutional access.

Scholars have long debated the inequities in traditional academic publishing. Suber (2012) highlights the barriers created by expensive subscription models, noting that access to knowledge becomes a privilege rather than a right. Willinsky (2006) argues that open-access publishing broadens the reach of scholarship, allowing not only academics but also the general public and researchers in developing nations to benefit from cutting-edge research. Palmquist’s work is firmly rooted in this tradition of democratizing knowledge, ensuring that academic work is not constrained by paywalls or limited to well-funded institutions.

Palmquist’s commitment to open access aligns with the Xennial ethos of breaking down barriers and fostering inclusivity. By providing a platform where research can be shared without financial or institutional gatekeeping, the WAC Clearinghouse embodies a more democratic vision of scholarship. For Xennials who have witnessed the decline of traditional academic supports and the rise of digital networks, Palmquist’s work is a beacon of how new models can address longstanding inequities in academia.

The Xennial experience in academia is shaped by a trifecta of scarcity, digitality, and hierarchy. Scarcity, because state support for higher education has been steadily declining since the 1970s. Digitality, because nearly everything significant has shifted online since the mid-2000s. And hierarchy, because academia loves a good hierarchy nearly as much as it loves a cup of coffee and a good seminar paper. Amid these challenges, the rare phenomenon of a tenured professor taking on service roles and the pioneering work of figures like Mike highlight how Xennials are navigating and transforming the academic landscape. Embracing new roles and championing open-access publishing, we continue to bridge gaps and push for a more equitable and innovative future in academia.

Oh, today is my birthday! I am 44 years old today. Thanks for reading!

References

Suber, P. (2012). Open access. MIT Press.

Willinsky, J. (2006). The access principle: The case for open access to research and scholarship. MIT Press.