What a time to be sober.

Five years ago, I stopped drinking alcohol. Then the whole world split apart.

On February 5, 2020, I quit drinking. Five years later, I find myself reflecting not so much on personal transformation—though there’s been plenty of that, too—but on the world that has unraveled and reshaped itself in the time since. It’s hard not to. I guess that’s the only downside of sobriety: everything is a little clearer when you’re sober.

A month after I stopped drinking, the world shut down. The pandemic redefined daily life and politics; social isolation became a necessity. Heavy alcohol use among Americans rose by 20% during the pandemic.

Then came the upheavals, both personal and world-historical—more political turmoil; the attempted insurrection on January 6, 2021; divorce; Russia’s invasion of Ukraine; Joni’s passing; the war in Gaza; the fall (and rise) of Trump and with it the implosion of anything like a center-left party in US politics; economic volatility and historic inflation; a housing market so wild it became a meme; the loan assumption process; extreme weather, drought, flood, fire; ChatGPT, and now its cheap(er) Chinese knock-off.

Here’s one thing I’ve learned. Sobriety isn’t just about the continued state of not drinking. It’s not an absence at all, really; it’s about presence. It’s about making it through elections, social unrest, and a hundred personal failures and triumphs with clear eyes, or about having the discipline to finish my first book (shameless plug: Misinformation Studies and Higher Education in the Post-truth Era: Beyond Fake News is out now!) and keep going even on those days when it would have been easier not to. It’s about showing up no matter what.

Five years in, I can say this with some confidence: sobriety is both ordinary and radical. Ordinary, in the sense that life continues. Emails arrive, papers need grading, shoes need selling, dishes need washing, deadlines loom, students carp. Students always need something from you. (It’s nice to be needed.)

Radical, in the sense that it has changed everything. It has given me back time, energy, and clarity. It has forced me to confront things I once avoided. And it has given me the ability to stand in the world, fully present.

What I didn’t totally anticipate was how sobriety would recalibrate my relationship with ambition and productivity. The work I do now is deeper, more deliberate. I’ve traded in the frenetic bursts of productivity fueled by rogue anxiety (and occasionally, alcohol), which long ago I believed was essential for this kind of life, for something steadier and ultimately more sustainable. Writing the book, for example, wasn’t just about assembling words on a page or reaching the final goal of publication—it was about building trust in myself, day after sober day, to get the hay in the barn.

Or something like that.

And then there’s joy. The kind of joy that doesn’t need to be manufactured or chased. It’s in small things—an early morning run when the city is still quiet, a conversation with a friend, the feeling of actually being there in my own life. Like a lot of people who drink, I used to think sobriety meant giving something up. But at five years in, I see it for what it really is: a widening, an opening, a portal back to myself.

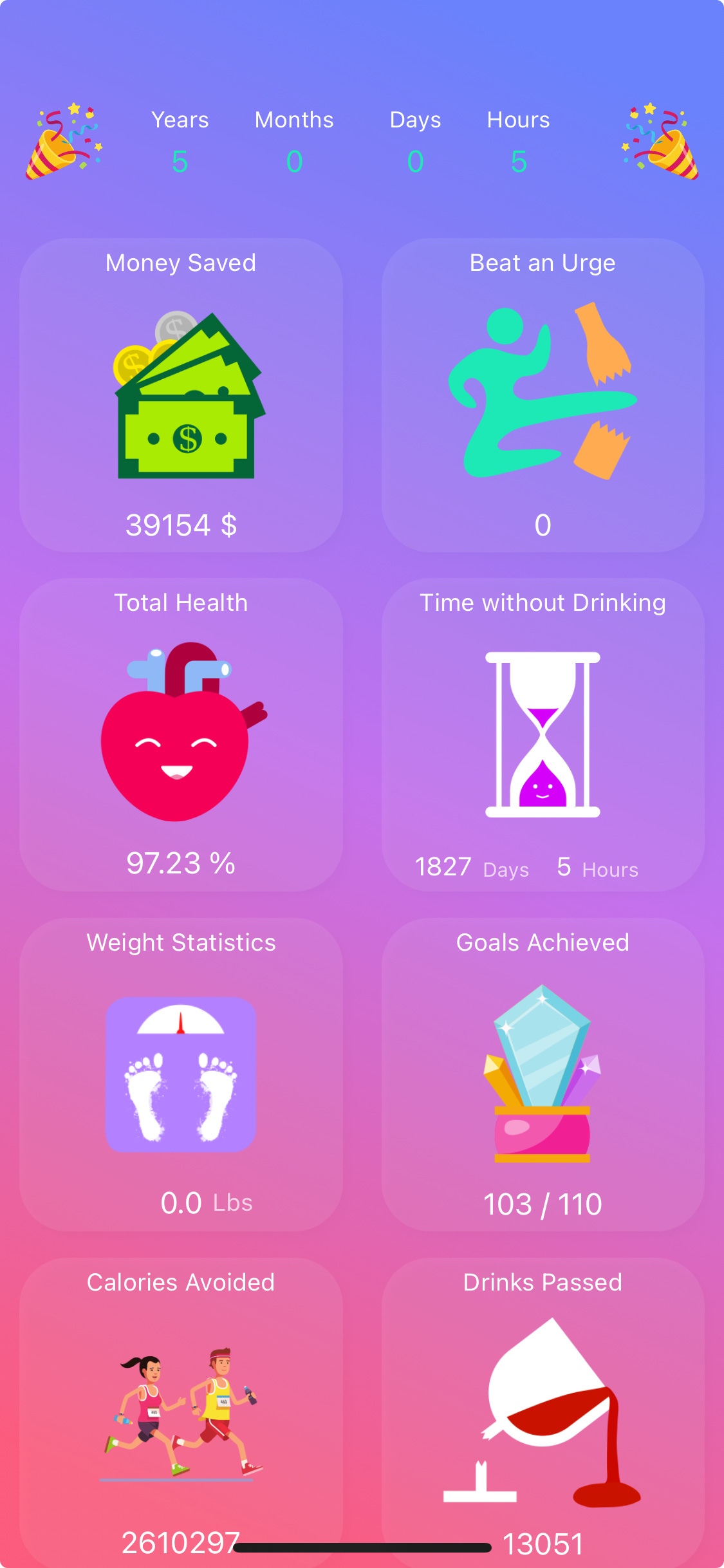

I’ve saved nearly $40,000. (And avoided 2.61 million unnecessary calories.)

In one of my all-time favorite books, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, Robert Pirsig writes of his search of everlasting quality: “The only Zen you find on the tops of mountains is the Zen you bring up there.” It’s like this. Sobriety, like Pirsig’s ideal of quality, isn’t an external prize waiting for you at the finish line. Sobriety is the process. It’s something you have to bring with you: in each decision to stay present, each moment of clarity, each small act of patience and self-respect. If the past five years have taught me anything, it’s that meaning or substance or quality—call it what you will—isn’t found in grand gestures or self-serving blog posts. Rather, it’s in the quiet work of showing up for yourself, over and over again.

There’s a common way people talk about sobriety, as if it’s a process of climbing out of some dark abyss and stepping into the light, like the captives in Plato’s cave allegory—triumphant, even boastful—with a neatly resolved narrative arc. Happily ever after.

But I try not to think of it that way, tempting as it is. If anything, sobriety feels less like climbing out of a hole and more like realizing the abyss wasn’t what I thought it was. The world didn’t become brighter and more orderly just because I quit drinking. The world was always chaotic, contradictory, and strange. I had just been dulling my place in it. Sobriety didn’t give me clarity, but it did give me the chance to earn it, and for that I am grateful.

And here’s the thing people don’t say enough, especially as sober-curious (TM) becomes an influencer-led cottage industry: sobriety isn’t just about self-improvement or “becoming the best version of you” or whatever the flavor of the month mantra happens to be. It’s not some noble, monk-like discipline with moral superiority as the grand prize (though this is precisely how some people online treat it). It’s weirder and funnier and more random than that. Sobriety means learning to sit in boredom. It means remembering, in real time, exactly why you used to drink in the first place. It means doing battle with waves of FOMO. It means finding new ways to socialize and “find your tribe,” which sounds like something an influencer would write. Sometimes life is awkward and absurd and heartbreaking. Being fully present for it is its own strange challenge. Sobriety is watching the world unravel in real-time and realizing, with some mix of what I can only describe as horror and wonder, that you don’t need a buffer between you and it anymore.

Something tells me that’s not quite the hero’s journey Carl Jung talked about—it’s just living. And honestly, that’s been enough.

So today, I celebrate. Five years. A timeframe so momentous Bowie even wrote a song about it. A milestone that, once, felt impossible. And if you’re reading this, whether you’re sober, curious, or simply reflecting on your own journey through the past five years, here’s what I can tell you: life on the other side is worth it.

Thank you for reading. Now, a few quick professional updates:

As I mentioned, the book is out. Well, in eBook form. The hard copies are supposed to arrive by mail any day now. In fact, I was on a meeting with Bruce yesterday when his freebie review copy arrived in the mail. Still waiting for my copies. If you’re with Indiana University, you can access the entire eBook via IU Libraries with access for all nine campuses.

Speaking of, Bruce and I are hard at work on a new project: an edited collection entitled The Post-Truth Handbook: A Practical Guide to Addressing Disingenuous Rhetorics. We’ve managed to wrangle a top shelf cadre of scholars and academics for this collection and, to be blunt, we’re fighting off academic publishers like Routledge with a stick. The level of interest in the project is high, so it will be interesting to see who we finally go with as our publisher. And it’s always nice to be courted.

My piece on failure studies, “Genealogy of Failure,” appeared a couple of months ago in the edited collection If at First You Don’t Succeed? Writing, Rhetoric, and the Question of Failure (WAC Clearinghouse, 2024), a volume in which “25 writing studies scholars use failure as a conceptual lens to reflect on their experiences as scholars and teachers. Their contributions address historical and theoretical treatments of failure, offer case studies of failure in teaching and research, and share brief (but bitter/sweet) narratives drawn from personal experiences in the field” (from the publisher).

Congratulations on such an amazing accomplishment and milestone! Thank you for sharing such a vulnerable and insightful piece. I’ve been waiting for well over a year now, and I can’t wait to read your book. Congratulations on everything!

Congratulations on 5 years! Proud of you for making that decision. You did a fantastic job of explaining the impact of giving up drinking.