What Is an Expert?

Everybody's dunking on the CDC, but our democracy needs experts now more than ever.

Just a couple of days after Christmas, the CDC released a now-infamous set of updated guidelines recommending that those infected with COVID-19 shorten their time in quarantine from ten days to five days.

According to the media statement,

The change is motivated by science demonstrating that the majority of SARS-CoV-2 transmission occurs early in the course of illness, generally in the 1-2 days prior to onset of symptoms and the 2-3 days after.

I first heard about the new recommendation on NPR and thought it was odd timing. Or really just odd all the way around. Cases had been steadily rising since November, with a spike between Christmas and New Year’s Day that has only become more pronounced in the last few weeks.

Why would you advise COVID-positive people to cut their quarantine time in half?

Not only that, but history clearly showed a pronounced uptick in cases the previous holiday season, too—that is, Christmas 2020—back when many Americans were still taking precautions like social distancing and quarantining at home as much as possible. (Heck, I know of a handful of people who used the pandemic more or less as an excuse to get out of having to travel across the country to spend time with family in Pandemic Year 1.)

But, I thought, it’s the CDC for crying out loud. Surely the venerable Centers for Disease Control is following sound science in making these pronouncements. Efficient messaging might not be the bureaucracy’s strong suit—most of us who’ve been paying attention would agree they have a checkered past in the communication department —but they’re scientists for crying out loud. They’re not supposed to be the world’s greatest communicators. Their expertise lies elsewhere.

Plus, we now know the Trump Administration had been interfering with the CDC since the early days of the pandemic, pressuring officials to alter reports and pushing them to release guidance that people who were symptomatic should not get tested.

Whether due to political meddling or not, at times the recommendations that the CDC and Dr. Anthony Fauci have issued over the last two years has been baffling, poorly-delivered, and just plain wrong. One notorious example is Fauci’s early advice in February of 2020 to not wear masks, a grave error for which he (and by extension the rest of the country) is still paying a heavy price.

Experts get things wrong. Falsifiability is a key feature of science and the advancement of knowledge. When you find out that maggots aren’t spontaneously generated from spoiled meat, as no less an expert as Aristotle once theorized, then you throw out that theory and move on to the next one.

The Latin root of our English science is scientia, or knowledge. When an operative theory for explaining the natural world is no longer considered knowledge, it is no longer considered science.

Still and all, this most recent head-scratcher from our top infectious disease experts seemed to be the last straw in a long line of bungled messages.

Naturally, the Twittersphere didn’t miss a beat. A whole raft of “The CDC says…” jokes ensued.

Ouch. That one hits home.

Late night comics, never ones to miss out on the pandemic zeitgeist, also got in on the merriment.

This most recent episode in our great national unraveling has me wondering about the nature of expertise, a topic I presented on earlier this week at the AAC&U annual meeting in Washington, DC.

The theme of this year’s conference was “Educating for Democracy,” and I was invited to be part of a panel on deliberative dialogue as a way to engage students on questions of central importance to democracy: immigration policy, global climate change, Roe vs. Wade, and other such cuddly topics that students are always jumping on top of their desks to talk about in the classroom.

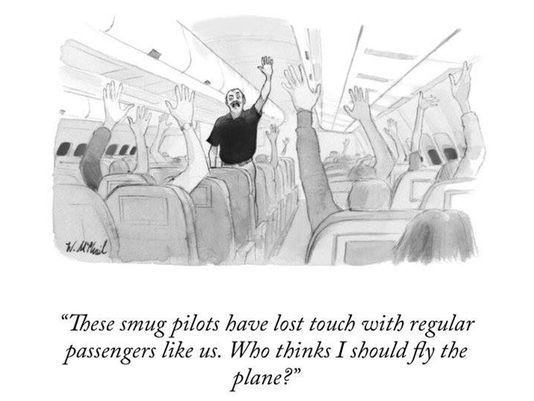

Specifically, my talk centered on who gets to call themselves an expert in these complicated times and, perhaps more to the point, who gets to enjoy the privileges of expertise. Who do we listen to these days? Why? How can we use examinations of expertise and authority in classroom discussions as a way to understand how “who gets to speak” on a particular issue shifts and morphs across disciplinary contexts? And what is the relationship between these fundamentally epistemological questions of who knows what and how and our grappling with the challenges of living in a representative democracy?

Fauci provides a useful example—and has since the earliest days of the pandemic. The man has impeccable bona fides and unassailable credibility. His work on HIV/AIDS in the 1980s alone qualifies him as an expert in immunology and infectious diseases, and no less an authority than Fauci’s Wikipedia entry has the following to say about Fauci’s citations in the scientific community (citations are the number of times a researcher’s published work has been cited—or used—by other researchers):

In 2003, the Institute for Scientific Information stated that from 1983 to 2002, "Fauci was the 13th most-cited scientist among the 2.5 to 3.0 million authors in all disciplines throughout the world who published articles in scientific journals." As a government scientist under seven presidents, Fauci has been described as "a consistent spokesperson for science, a person who more than any other figure has brokered a generational peace" between the two worlds of science and politics.

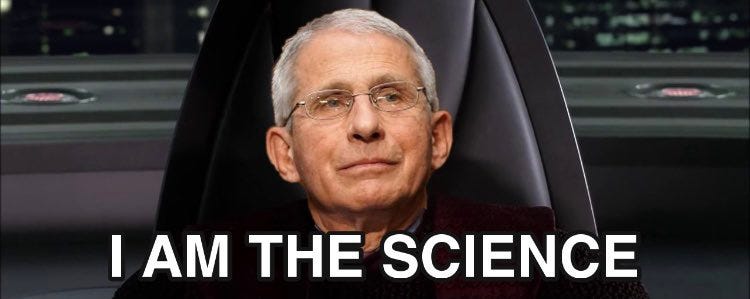

Ten days ago, Fauci and his longtime nemesis Sen. Rand Paul (R-KY) got into another bafflingly incoherent exchange on Capitol Hill when the Republican Senator began pummeling Fauci with the Right’s latest storyline, which is apparently to make it seem like Fauci is a power hungry megalomaniac who thinks of himself as Science Incarnate. (Science Incarnate, incidentally, is also slated to be a new Marvel supervillain played by Rick Moranis opposite Robert Downey, Jr.’s Tony Stark/Ironman. (Jokes, jokes, jokes.)

This is ironic, given the Right’s continued obsession with another power hungry megalomaniac named Donald J. Trump (perhaps you’ve heard about him?). But I suppose this is the best they can come up with on short notice.

You can watch the Fauci-Paul exchange in its entirety here:

Since ancient times, the nature of expertise has been a hot topic in discussions about public policy and democratic engagement. Socrates and his interlocutors in Plato’s dialogues, notably the Gorgias, the Phaedrus, and the Apologia, spend literally hundreds if not thousands of lines of ancient Greek text debating the relationship between the expert and the deliberative power of the demos (the people), especially as it relates to questions that impact the common good. Indeed, this preoccupation with who-knows-what-and-how is often one of the features of Platonic dialogues that make them so tedious: Socrates is always asking these long-winded questions concerning who knows what, and who is in the best position to know what, and what precisely gives them the authority to claim that they know best, and how that know-how differs from other kinds of know-how and why, and so forth ad infinitum.

In other words, authority, expertise, and democracy are closely intertwined, and I am interested in exploring these connections with students, particularly as this matrix relates to teaching about misinformation.

Authority—expertise, by another name—is constructed and contextual. Using expertise as the basis for how we assign value to a speaker’s utterances, whether politician or bystander or Twitter gadfly, is a useful mechanism for exploring veracity and credibility that doesn’t automatically become a war of competing headlines or claims. How might using questions regarding expertise (re)animate our discussions in the classroom regarding misinformation and the kinds of sources students—and citizens—should trust.

I’ll be writing more about this topic of expertise, democracy, and misinformation in the near future, so consider this newsletter a “Part I of X” kind of entry. (“X” here means I don’t know how many parts there will be; it’s not a Roman numeral, in other words.)

Have a great rest of the week, everyone.

What do you think? What is an expert? Leave me a comment. I would like—nay, love—to hear from one of my readers. And if you don’t leave a comment, at least have the common decency to subscribe to The Highlight Zone.