Remember that guy who infamously bragged to #AcademicTwitter about how many articles he had published as a graduate student?

I wish I could find the original tweet, but apparently my digital literacy skills aren’t as sharp as I thought they were. (If anybody has it bookmarked—and if it hasn’t been dunked clean out of existence—please send it along.)

Fortunately, you don’t have to go back to 2021 to find examples of the productivity bug. It always seems to be going around this time of year, especially on Twitter and wherever else academics congregate to humblebrag. Among the lush gardens of predictable tweets about losing weight and getting fit, this New Year’s season has yielded a bumper crop of productivity discourse.

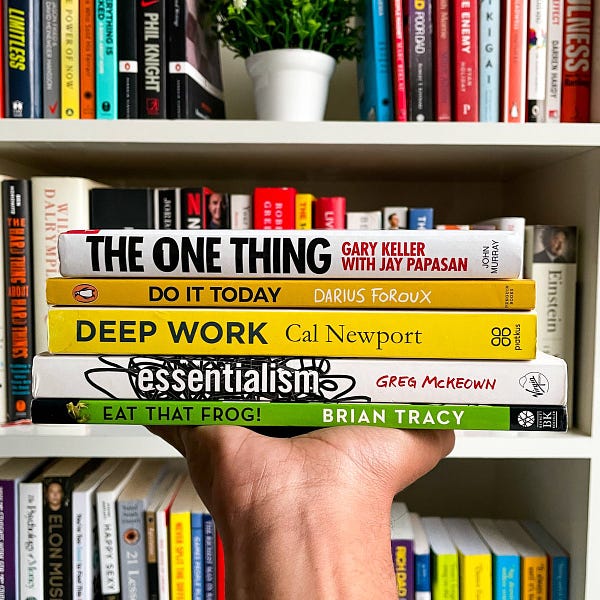

There are tweets recommending books on productivity:

Tweets that recommend productivity apps and schemes:

And, of course, a hefty amount of ironic humor, too:

Don’t forget the hilarious memes!

Lurking just underneath the surface of all this is a deep unhappiness. I suspect that’s the case because I feel it, too. As someone on social media is always just seconds away from reminding everyone, we survived a pandemic, we made it through 2021, we are alive! We should be celebrating, this feeble attempt at a counter-narrative goes, just because we are here! Living, breathing, procrastinating, clicking through one more ream of tweets or watching one more show on Netflix before we get back to that article we are writing or the syllabus we’ve neglected or the Substack post that’s been rolling around in our heads since before Christmas.

We should be thankful to be alive, in other words, not sweating our lack of productivity.

If it were only that simple.

But this counter-narrative feels…weak, doesn’t it? Unconvincing? Sure, it’s great to be alive, breathing, moving, etc.—the alternative certainly doesn’t seem like much fun—but how many of us lost precious time with our families over the holidays because of that nagging, ever-present sensation that we should be doing something else?

How many of us are plain miserable now because we can’t seem to get back on the horse and next week (or the week after, if you’re lucky) brings with it the inevitable onslaught of classes and deadlines and 100+ emails per day? [Sigh.] Maybe this is just a function of the job, an unavoidable by-product of not being a clock-puncher or a technician with a more clearly defined sense of work-life balance.

Surely academia hasn’t always been this way…or has it?

Of course, there are many reasons why academic want to be more productive around this time of year, and not all of them have to do with writing and publishing (though from the looks of it, many do). But in this post, I want to focus specifically on the modern academic ethos of productivity regarding writing.

Patronage and Patrimony > Publishing

Some historical perspective on academic publishing and the history of universities in the West may be useful to this discussion.

Prior to the 19th century, university appointments were a matter of either family ties or social standing. Publishing didn’t really fit into the picture, it was more about how who you knew, who you were related to, where you fit into the social hierarchy, or how many exotic specimens or rare books you happened to own. Many of the earliest professorships were passed on from father to son, or they were the result of a complex system of patronage based on one’s place within the rigid hierarchies of British and European nobility.

So when did publication and, hence, productivity become such an indispensable part of the whole academic enterprise?

Historian William Clark, in his impressively comprehensive tome Academic Charisma and the Origins of the Research University, traces the origins of the “publish or perish” ethos in academia to Prussian universities in the mid-1700s, specifically to a regulation of 1749 that required three or more publications (analogous to contemporary journal articles) to be considered a viable candidate for a professorship (259-60). (An academic needed only three more to become a candidate for chair.)

As he dryly notes, “Publish or perish in 1749 thus did not necessarily mean books” (260).

This was the situation on the Continent, but British and American universities weren’t far behind. By the 1830s, the idea began to form that evaluating candidates for professorships on their scholarly productivity might be a more effective way to separate the wheat from the chaff, the scholars from the dilettantes, a learned entomologist from some duke with an unusually large bug collection.

Suffice it to say, the idea took hold for the same reasons that publication is still the primary way of evaluating academics today: it provides everyone involved—from grad students to assistant professors to university administrators—with the sense, rightly or wrongly, that there is a rhyme and reason to the way we keep score and mark time.

In other words, we’re not just making all this up.

Publications also provide a nifty way to deal with the fact that, going back centuries, there have been more people who want to be professors than there are positions. Just ask anyone who has been on the academic job market in the humanities in the last 40 years.

In a passage that reads like it could be written about the 2021-22 job market in English, Clark notes that even before the regulation of 1749,

competition over some positions had already led to swollen applications. In 1713 a candidate submitted a list of eleven numbered publications in his application. He claimed that others could not match his numbers. (260)

In a passage that reminds me of the last tenure-track job ad I read, Clark goes on to enumerate the kinds of documents that applicants would enclose:

In 1715 another applicant enclosed copies of his dissertation, copies of the lecture catalogue to document his teaching, and other enclosures. In 1735 a candidate noted he had worked “with all loyalty, zeal and diligence” and enclosed a separate sheet: “My few published writings to date,” with fifteen titles. An application of 1743 had a list of publications with twenty titles. (260).

Once the snowball starts rolling down the hill, it gathers snow and gets bigger. What was once suitable to land a tenure-track job, is now expected of a first- or second-year graduate student in some fields. What once would earn you tenure at a large state school, is now a prerequisite for application.

I have a theory that productivity discourse is even more pronounced among those of us who call rhetoric and composition studies (or “rhet-comp”) our disciplinary home.1 Rhet-comp is all about writing and writers: the social dynamics of writing, the history of writing and rhetoric, the myriad ways that rhetoric and rhetorical theory intersect with writing, the way writing informs and expresses identity, and so forth.

Writing is not just one thing among others for us. It is, quite unavoidably, the thing we do, teach, profess, and live.

So for someone in rhet-comp to struggle with writer’s block or procrastination or stunted productivity or to want to watch just one more episode of 90 Day Fiance rather than sit down to that article draft on responding to student writing is far more deleterious to one’s professional standing than, say, an economics professor who hasn’t published so much as a tweet since 2012. Not only do folks in rhet-comp feel the ever-present urge to write, but we feel as though we have to write well.

Sheesh. No wonder our Twitter feeds are so angst-ridden.

Actually, this is a theory born out of a conversation in my writing group, so I have to give credit where credit is due. Also, while we’re on the topic: writing group = productivity scheme.