Surf's Up (1971)

50 years on, the Beach Boys' most prescient and heartbreaking album is one for the ages.

Why is it that on every run I make to Aldi, I am hubristic enough to think that I can get away without plopping down a quarter for a shopping cart? I know full well I am going to buy way, way more than I can carry, even in my two hefty re-usable hippie sacks, and inevitably I find myself limping towards the checkout line like some broken down urban sherpa, schlepping my 50 pound haul of gummy bears, veggie chips, and frozen pizzas.

It is with the same hubris that I sit down to review an album that I have recently re-discovered as one of the best of all time (BOAT), from one of my favorite pop-rock groups, the Beach Boys. And all I can think as I write is, Who am I to review this masterpiece?

But first, what am I trying to do with this newsletter and what will this space be(come)?

I am a college writing professor who, earlier in 2021, became intrigued by the possibilities of Substack and of publishing a semi-regular newsletter on political and cultural takes, mostly, and the occasional album review, with a particular emphasis on current events that intersect with misinformation and our polluted information ecosystems. I am currently writing a book about the latter, but I have already written enough scholarship for the academy (you can check out a long and growing list of articles, essays, and book chapters here) to know that writing for an audience of seven people (hi, mom!) gets old real fast.

Years ago when I first moved to Indiana from Kansas (by way of South Carolina, my home state), I started a blog about local pizzerias that became popular with some of the locals in my area, and I briefly became known as “that guy who reviews pizza places” before handing it off to a former student of mine who is doing wonderful things with the space. I love blogging, don’t get me wrong, but one of the features of Substack that really intrigues me is the ability to get people to pay for your work the way they do Hulu or Netflix or NPR’s Wine of the Month Club.

Just kidding. I intend to keep the vast majority of my posts free of charge, especially as I am just getting my feet wet. While I may be hubristic enough to try to write a review of Surf’s Up, widely regarded as one of rock/pop’s best albums ever, who am I to charge people for my words? As a scholar and researcher, it goes against everything I value. Almost.

At any rate, I hope you enjoy this review and that you will consider subscribing to my newsletter. For the foreseeable future, I am going to focus on putting out one medium-quality post each week. Enjoy!

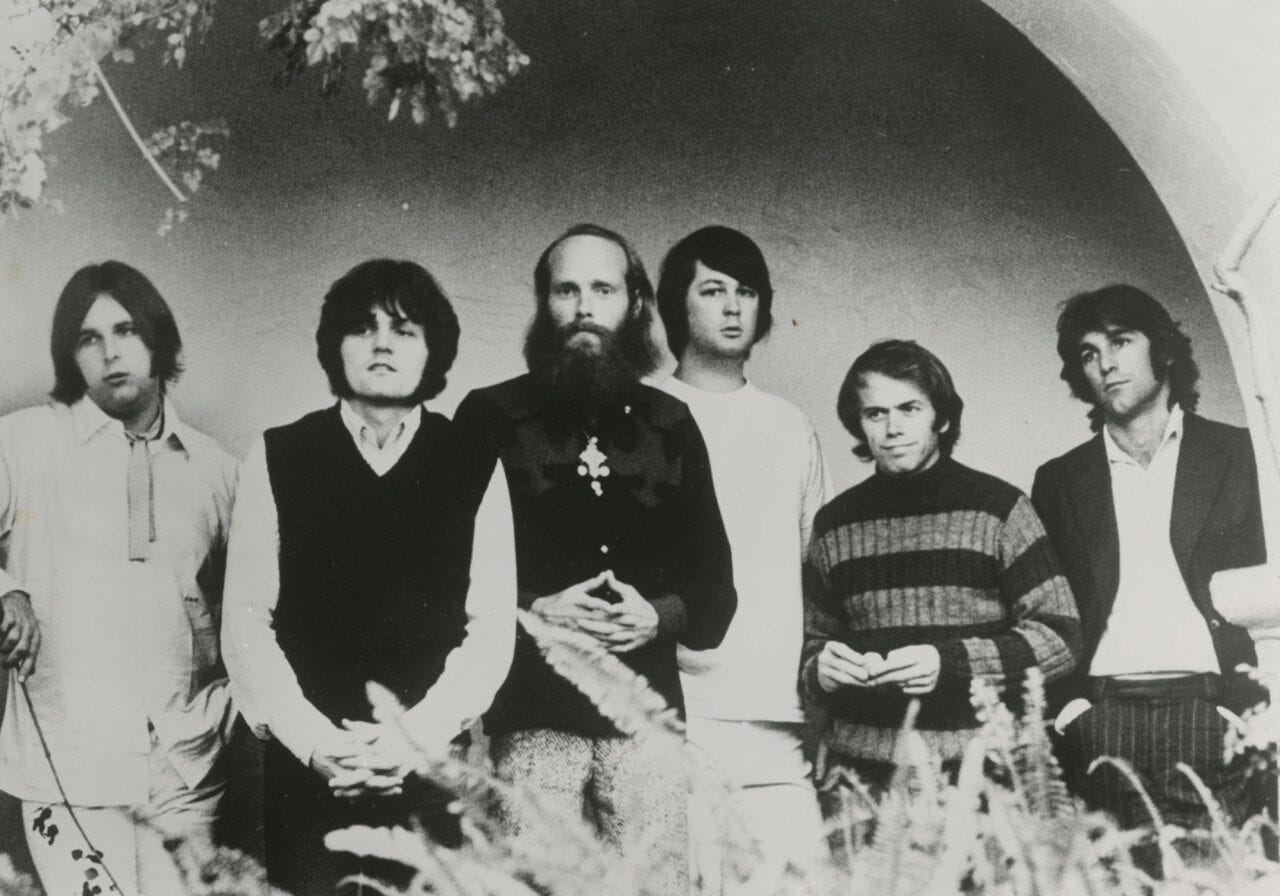

By the dawn of the 1970s, the Beach Boys, once a formidable (and bankable) touring and recording operation, had all but washed ashore. The heady days of the mid-60s—playing sold out venues worldwide and releasing multiple chart-topping singles and albums every year—were already a distant memory. Musical tastes had changed rapidly in the years since 1966’s masterstroke Pet Sounds. The war in Vietnam was escalating. The counter-culture was on the rise. The youth of America were no longer impressed with a clean cut group in pin-striped shirts singing about surfer girls and hot rods and tasty vibes.

Not only that, but against a backdrop of war and student activism and drug culture, the Beach Boys seemed…anachronistic. The group was in serious danger of becoming a variety act you might catch on late night television or The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour alongside John Wayne or Phyllis Diller. To make things even more challenging, a bitter contract dispute with Capitol Records, which had been the group’s recording home since the early 1960s, had resulted in original band dad Murry Wilson selling off the entire back catalogue for just $700,000.

Even the Wilson boys’ father believed the group was washed up.

We’ve all seen the ‘60s montages. The Beach Boys’s schtick was tired. And the band knew it.1 To make matters even worse, the 1970 album Sunflower, their first on their new Brother Records label, turned out to be the worst-selling record in Beach Boys history.

But not all was lost. The vocals were still tight as a snare drum. The arrangements were golden and complex. Brian Wilson was still a genius. Troubled, yes. But all the same a songsmith on par with the likes of Paul McCartney and John Lennon—two world class songwriters with whom Wilson and the boys had engaged in friendly competition since the release of the Beatles’ Rubber Soul in 1965.

So the band fired their promoter and co-manager, lost the corny pin stripes, and on August 30, 1971 released an album second only to Pet Sounds in its sheer brilliance, musical ingenuity, and topicality.

In the album era, artists typically stuck with the traditional two-sided format. That is, while each album was meant to be a complete artistic statement, it was self-consciously composed of two halves or “sides,” and typically each side had its own flavor.

Side 1 of Surf’s Up contains the more upbeat tunes, starting with the pseudo-psychedelic pop jangle of “Don’t Go Near the Water,” a song about environmental degradation that signals the group’s turn to more serious subject matter as well as a transition away from the lighthearted surf tunes of the early- to mid-1960s.

Written by Al Jardine and Mike Love, the basic idea of “Don’t Go Near the Water” is that if people can’t take care of the water, which is a metonym for the environment writ large, then they have no business using it for fun and frivolity. This must have been a shocker of an opening track at the time coming from a group whose entire musical success was a result of touting the recreational benefits of water sports, namely surfing, but also just the whole SoCal beach bum/fun-in-the-sun image. (I mean, the name of the band is the Beach Boys for crying out loud.)

Next up, the Let It Be-inspired ballad “Long Promised Road,” sung by Carl Wilson, is probably the highlight of this side of the record, and a worthy showcase for Wilson’s lofty tenor and burgeoning songwriting skills. Carl, who died from complications from lung cancer in 1998, lived in the long shadow of brother Brian. But on this track, as on side 2’s “Feel Flows”—another song he wrote and provided lead vocals on—his star shines nearly as brightly as anything else Brian put to music, with the possible exception of “Surf’s Up.”

Brian and bandmate Al Jardine sing lead on the goofy “Take a Load Off Your Feet,” the album’s third track, and an ode to what in 2021 we would call “self care.” It’s easy to dismiss this little ditty as something of a throwaway, good time little tune, but it’s clever and has an absolutely infectious melody that you find yourself humming or singing full bore around the house, much to the chagrin of your family. The musical Hair was getting rave reviews at the time, and someone in the band suggested a mild parody song about ankles. This quickly turned to a song about feet, and thus, “Take a Load Off Your Feet” was born. “Disney Girls (1957)” is similarly gimmicky but musically much more satisfying, with lyrics expressing an earnest longing for a simpler time amidst the turmoil of the era. It is the first real inclination of the deeper, more existential themes to come on the album’s second side.

“Student Demonstration Time” is by nearly all accounts the low point of side 1 and, honestly, probably better off skipped altogether after you’ve heard it at least once. The song, with its ripped-from-the-headlines lyrics reportedly embarrassed Carl Wilson, and it is easy to see why, especially in retrospect. The lyrics reference the Kent State shootings of May 1970 in which the National Guard fired on a crowd of anti-war protestors, killing four students and seriously wounding several more.

Admittedly a low point in US history, one that, arguably, rivals January 6, 2021, other musicians at the time covered the song, most notably Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young in their classic “Ohio,” which was released just weeks after the massacre. But whereas the CSN&Y song comes off like an authentic exploration of the zeitgeist, “Student Demonstration Time” feels contrived. It’s as if the band decided “Hey, let’s sing about student activism and anti-war protests—that’s what all the kids are talking about these days.” For me “SDT” is the musical equivalent of that Steve Buscemi meme “How do you do, fellow kids?” that was all over the internet a couple of years ago.

Musically and lyrically, “SDT” is an update of the ubiquitous R&B standard “Riot in Cell Block 9,” which is precisely what Love—who wrote the lyrics and also provides the lead vocals—intended it to be. It’s got an upbeat rhythm and blues tempo with some cool theremin-inspired siren effects thrown in. But if you listen closely to the lyrics, while the song purportedly is about student demonstrations, it’s also warning people to “stay away when there’s a riot going on,” suggesting that even when attempting to be politically relevant and hip to the beat, the Beach Boys couldn’t help but be square.

Kicking off side 2 of the album is “Feel Flows,” another Carl Wilson composition on which he also supplies the lead vocals. It’s all gravy for the rest of the record. After the contrived mess that is “Student Demonstration Time,” the album’s second half is where things start to get serious.

One reddit user summed it up nicely:

“When ‘Feel Flows’ starts up it's like plunging into an ice cold lake after being set on fire. Bliss.”

As one of the longest songs in the entire Beach Boy’s catalogue, “Feel Flows’” nearly five-minute run time feels like the blink of an eye, which is a testament to its brilliance. It is an undisputed highlight of the album. The song begins with a trippy, synthy organ and piano intro and carries its jazz-rock sensibility throughout the track, incorporating flute and saxophone and a bevy of largely nonsensical, psychedelia-laden lyrics. “Feel Flows” is simply like no other song the band ever performed (though it feels a bit like a trippier “Good Vibrations”), and it sends a clear signal to the listener about what to expect for the rest of the album.

"Lookin' at Tomorrow (A Welfare Song)" is a brief, barely two minute throwaway tune that serves primarily as Jardine’s last word before the start of Brian’s three-song cycle that winds down Surf’s Up, a trio of songs that were written expressly as a response to McCartney’s medley at the end of Abbey Road. “A Day in the Life of a Tree,” titularly an homage to the Beatles’ “Day in the Life,” furthers the theme of environmental destruction that the albums plays around with in sporadic fashion.

In 1970, the Nixon Administration had just chartered the Environmental Protection Agency; the Cuyahoga River outside Cleveland, Ohio had spontaneously combusted into flames (again) just a couple years prior, and Rachel Carson’s 1962 bestseller Silent Spring brought awareness of the dangers of pesticides to millions. Brian Wilson was increasingly concerned about the destruction of the earth’s natural resources and polluted environment, and “A Day in the Life of a Tree” makes good on these themes in a song sung from the perspective of a tree that feels itself to be dying.

As if fearing that an existential song about death from the perspective of a tree wouldn’t be obvious enough, next up is “Til I Die,” arguably the second most gorgeous song on the album. It starts out conventionally enough, but by the end, as Brian starts layering on the vocals, the song has the potential to bring you to your knees.

“Surf’s Up,” the album’s final track, is, quite simply, Brian Wilson’s masterpiece, and the lore surrounding the writing, singing, and recording history of this song is well worth spending an afternoon reading about (start with the Wikipedia entry and go from there). The song was written as a counter to the Beatles’ “A Day in the Life” that closes out the Sgt. Pepper album, and it matches that tune note for note in terms of sheer musical brilliance.

“Surf’s Up” was written and first recorded back in the mid-1960s and was initially intended to be included on the aborted Smile project. For years Brian avoided including the song as part of any official Beach Boys release, until one day he changed his mind while putting the final touches on Surf’s Up (the album). Melding different time signatures with classical influences and lyrics that are first appear as completely nonsensical (and yet ultimately make perfect sense), “Surf’s Up” is the finest single track the group ever recorded. Sure, people will talk about “Good Vibrations” and the pop brilliance of “God Only Knows” or “I Just Wasn’t Made for These Times,” but taken as a whole, “Surf’s Up” is about a perfect an end to an album as you can find. It’s a gorgeous piece of music and a bright spot in the history of pop.

“The laughs come hard in auld lang syne.” Brian Wilson, “Surf’s Up”

This could be the caption as we bid farewell to 2021.

Surf’s Up merits repeated listens. There is simply no way around this. Some of the tracks, notably “Don’t Go Near the Water” and “Disney Girls (1957),” may seem overly simplistic and cloying at first. (In the hands of a lesser songwriter and arranger, they would be.) But they’re redeemed by the interludes. Check “Disney Girls (1957)” around the two-minute mark to get a sense of what I am talking about here. Just as you think the song has shown you all its moves, it surprises you with stunning beauty.

The best way to read Surf’s Up, some fifty years after its release, is as a coda on the activism and social upheaval of the 1960s and, at the same time, a commentary on the Beach Boys’ metamorphosis from surf party house band to serious chroniclers of a dream that had been perverted by the forces of old and evil.

Gone were the innocent days of the post-WWII economic boom, burger stands, and cruising the strip in a tricked out Chevy or scanning the horizon for the perfect wave. As the US involvement in Vietnam became more embroiled and unease at home became enmeshed in the everyday experience of ordinary Americans, so too did the dawn of the 1970s bring with it a crashing of a metaphorical wave, not unlike the one immortalized in Hunter S. Thompson’s famous “wave speech.” The latter appearing in Thompson’s infamous postscript on the 1960s in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, first published around the same time Surf’s Up was released in the pages of Rolling Stone magazine.

It seems that by the end of ‘71, everyone who was paying attention knew deep in their bones that the grand social experiment of the 1960s—whatever it was supposed to be—was indeed over. Altamont, Vietnam, Nixon, stagflation, acid rain, death, planetary destruction, and a coming fuel crisis were just a few of the noxious highlights of this era. Today, social historians and economists point to the early 1970s as the turning point at which the post-WWII tidal wave of economic expansion, union participation, fair wages, and the dream of the Great Society turned in on itself like a massive barrel wave and rolled back into the vastness of the historical abyss. Surf’s up, indeed.2

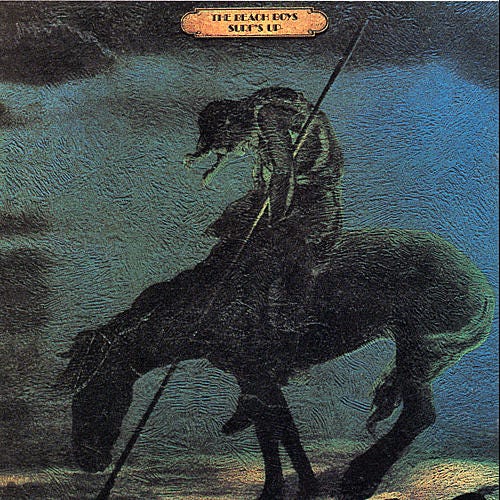

In that spirit, I want to close by considering the iconic image that graces the cover of Surf’s Up. The image is a two-dimensional reinterpretation of a piece of public art. James Earle Fraser’s End of the Trail is a sculpture located in a small town in Wisconsin—a strange location, perhaps, for a piece of art that depicts a weary Native American atop a horse.

The sculpture comments on the displacement of indigenous people from lands that were always-already theirs. The man, (world) weary and broken, faces west, towards the Pacific. The end of not only the trail but of the North American continent. There is no more land, nowhere else to go, no more worlds or lands to be conquered. Westward expansion and the colonizer’s religion of Manifest Destiny runs its course; the country founders, the American Dream turns back on itself in a hideous and violent parody. Fifty years later, embroiled in political extremism, mob violence, mass shootings, and a deadly pandemic that threatens to go on forever, the figure on the horse could be a symbol for our own era.

The image is profoundly fitting for an album that marks a turning point for the Beach Boys: a rejection of their surfer roots, which were always mostly phony anyway, their surf rock past, and the innocent hope that characterized the mid-twentieth century.

But more than that, the cover of Surf’s Up could also depict a national loss of innocence and faith, a creeping realization that the future would be bleak, and a shared understanding that the trail, insofar as one could even be found, would be fraught with existential difficulties. Democracy was never supposed to be easy and carefree anyway. [ ]

There’s a lot you could do with the whole SoCal culture and its uneasy relationship with the rest of the United States over time—culturally, politically, socially, etc. As much as people love the sun and surf and taquerias of Southern California, historically, the culture of the American Promised Land has long been at odds with the rest of the country.

It’s worth noting that the phrase “surf’s up” has a double meaning that the album gleefully exploits. Long understood as a phrase among surfers to indicate that the tide is ready for surfing, the phrase can also be taken to mean that the time for fun and games has come to an end, that it’s time to get serious about life.